The Mimblewimble white paper provided the foundations of the protocol. During the development of working implementations of the protocol, the devil that was in the detail necessitated a few deviations and finessing of the original design. Some of these changes are introduced and discussed in this article.

This article focuses on vanilla Mimblewimble. Tari has introduced several other additional features to the Mimblewimble protocol that are not covered here, including TariScript, output burning, and revealed values.

Table of Contents

Blocks

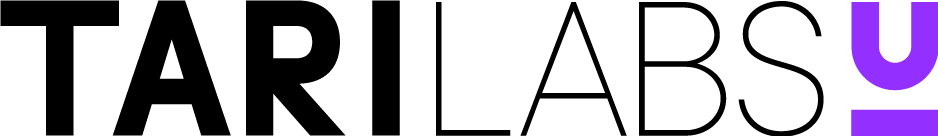

The anatomy of a Mimblewimble block is as follows:

There are two parts two a block: The header, and the body. The body is further subdivided into the inputs, outputs, and kernels.

Block Header

The block headers’ main function is to provide the proof of work. The do this by

- forming a chain all the way to the genesis block via the

previous_block_hashfield, - providing a proof of work.

The block header also serves some secondary functions:

- Keeping track of the accumulated offset.

- Committing to the state of the output set, input set, kernel set and range-proof data.

- Recording useful block metadata, such as the block height and timestamp.

Once you are in possession of all the headers, you know if any competing chain should replace the incumbent chain by virtue of having done more work. You do not know if all the transactions in the chain are valid. For that, you need the UTXO set.

Block Body

The block body contains the inputs, outputs, and kernels. Interestingly, the structure of a block body and a transaction body are identical, and Mimblewimble implementations including Tari, use the same data structure for both.

The set of inputs in a block or transaction are all former unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs). Since they are being spent in the block, they will shortly become _spent) transaction outputs (STXOs) and by Mimblewimble rules will be eligible for pruning.

The outputs in a block define the new UTXOs that are being created. They are accompanied by a range-proof and will be added to the existing UTXO set. The sum of UTXOs in the set must always equal the total emission of coins via block rewards. If this is not the case, the block is invalid and will be rejected.

The kernels provide important pieces of information that are critical for maintaining the integrity of the blockchain.

- The kernel signatures ensure that all parties involved in the transaction are happy with the state of the transaction.

- The total excess of the transaction (i.e. the sum of all the blinding factors of the commitments involved in the transaction) is tracked in the kernel.

- Additional metadata, such as the fee and kernel features are also recorded in the kernel.

Transaction kernels

You may wonder why the kernel data must be stored separately from the UTXO. Kernels are a necessary evil in what is otherwise a very elegant cryptocurrency protocol.

Nodes must always be able to calculate the accumulated excess in order to validate the overall balance. Since the kernel excesses are committed to, and stored in the kernels, the can never be pruned.

The kernel signature also allows us to check that owners of UTXOs okayed their spending. Note that the signatures merely confirm the excess commitment and are not connected to the inputs or outputs. So in theory, if a kernel signature was invalid you wouldn’t be able to know which inputs and outputs the invalid kernel was referring to. The whole block would have to be rejected.

Thought experiment - miners stealing funds

Question

Can miners split UTXOs up, so that the total balance is the same, but the spending keys are different?

E.g. replace

$$ C = k.G + v.H $$

with

$$ ( (k-k_s).G + (v-v_s).H ) + ( k_s.G + v_s.H) = C_w + C_s $$

The idea here being that miners can then steal v coins because they know the blinding factor \( k_s \). The other commitment

$$ C_w = C - C_s $$

is “waste”, since the blinding factor is unknown, but the villain doesn’t care about that.

Answer

The answer is no, miners cannot, because of the range proofs. Generating a valid range proof requires knowledge of the blinding factors. Since the miners do not know \( k-k_s \), they cannot create a valid range proof for the waste commitment.

Another thought experiment - miners manipulating UTXOs

Can miners remove some UTXOs but keep the balance the same?

E.g. A -> B, B -> C+D, miners remove B completely.

Yes, it’s called cut-through, and it’s allowed in vanilla Mimblewimble.

Thought experiment 3 - cut-through shenanigans

Can miners perform cut-through to spend funds to themselves?

E.g. A -> B, B -> M, miners remove B completely.

Answer

While miners can perform cut-though on the inputs and outputs, they cannot remove any kernels without breaking the overall balance. They also cannot tamper with the kernels because they cannot forge the kernel signatures without knowing the blinding factors of all the parties involved, which includes Bob.

In particular, miners would not be able to create a kernel for the B -> M transaction without Bob’s involvement.

Therefore, miners cannot steal funds from Bob by using cut-through.

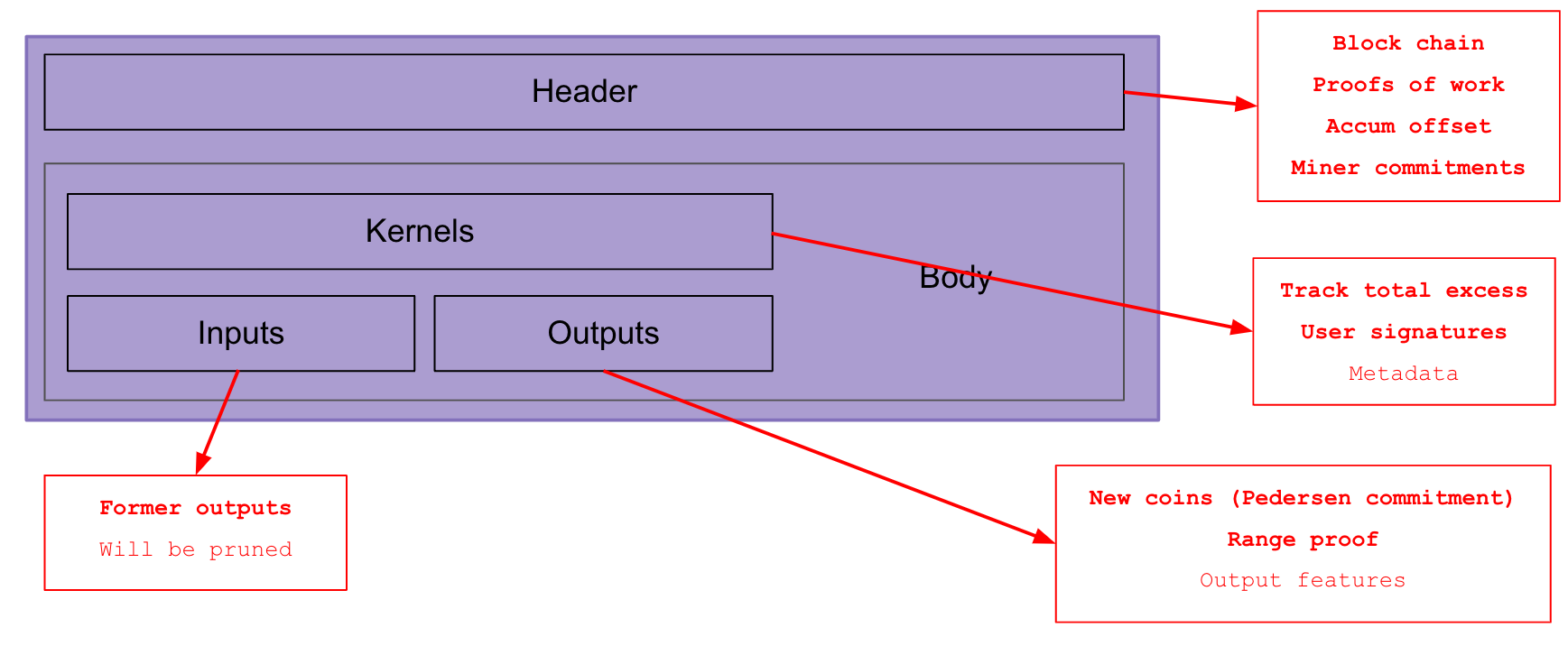

Data malleability

When miners construct blocks, they have the power to manipulate the block however they choose. It is therefore important to ensure that any tampering of data that we care about is detectable and disallowed.

Let’s consider the information in a Mimblewimble block and see which mechanisms are in place to prevent miner manipulations.

| Data | Malleable? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Range proof | No | Constructing a range proof requires knowledge of the blinding factor and commitment value. |

| UTXO value | No | The consensus balance will detect a changed UTXO value. |

| UTXO spending | No | The kernel signature will be invalid. The consensus balance will fail. |

| Transaction offset | No | The consensus balance will fail. |

| UTXO features | Yes | If an output is cut-through, there is no record of the features. |

| Header data | Yes | See comment below |

In general though, UTXO features are malleable in Mimblewimble and thus their application is highly limited. For example, in Grin, output features are limited to indicating whether an output is a coinbase or not. Since Coinbase outputs cannot be cut-through, this is fine. Any other information though, such as spending maturity on regular outputs could easily be ignored by miners.

Header data malleability

Miners are responsible for constructing the block header, and manipulating the header nonce is the primary means that miners use to perform the proof-of-work. That said, the data in the header, i.e. the MMR roots, previous block hash, proof of work data, timestamp, block height, etc., can all be verified post-facto by nodes. If the information is not correct and consistent, the block will be rejected and will not be used to extend the chain.

Outputs

Transaction outputs, specifically, unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs), represent the distribution of the supply of tokens at any given time.

Vanilla Mimblewimble outputs carry the following data:

- The homomorphic commitment representing the output amount

- A proof that the commitment value is positive

- The output features

The commitment

The commitment is the most important field, since it encodes that value of the output as well as identifying the output’s owner. Knowledge of the blinding factor and value is all that is required to spend the output in vanilla Mimblewimble. In Tari, this is not always the case, because of the additional flexibility provided by TariScript. We will not go into details here, but you can read more about TariScript in the TariScript RFC.

Range proof

Charlie, who is malicious, has an output containing 1 Tari. He sends -99 Tari to Alice , and gives himself 100 Tari in change.

1 -> -99 + 100

Since the values are blinded, in the absence of range proofs, this would pass all the Mimblewimble consensus rules.

Therefore, range proofs are required to ensure that this Enron-like accounting is prevented.

There’s another type of attack that, surprisingly, is thwarted by range proofs. Consider the following scenario:

A miner places a transaction into a new block, A -> C, spending commitment A to commitment C with some fee.

Somehow the miner knows that this transaction is Alice paying Charlie.

$$

A = v_a \cdot G + k_a\cdot H

C = v_c \cdot G + k_c\cdot H

$$

The public excess is

$$ X = k_c - k_a $$

and the kernel signature signs the message H(Ra + Rc || X || fee || m).

Now the miner adds a new output, M to the transaction, for reasons that will soon become clear.

M has zero value, i.e. \( M = 0\cdot V + k’ \cdot G \).

The miner then modifies commitment C so that things still balance.

Now the transaction looks like this:

$$

\begin{align}

A = v_a \cdot G &+ k_a\cdot H

C’ = v_c \cdot G &+ (k_c - k’)\cdot H

M = 0 \cdot G &+ k’ \cdot H

\end{align}

$$

The excess is now

$$

\begin{align}

X’ &= -k_a + (k_c - k’) + k’

&= -k_a + k_c - k’ + k’

&= -k_a + k_c

&= X

\end{align}

$$

The excess is still the same value as before! Therefore, the original signature with still validate the excess of this transaction.

However, now we’re in the situation that Charlie cannot spend his output, since he only knows \( k_c \) and not \( k_c - k’ \). The miner can now demand a ransom from Charlie for which he will reveal \( k’ \) allowing Charlie to spend his output.

Oh dear! Is Mimblewimble broken?

It turns out that we’re saved by an unlikely hero: the range proof!

The only way to generate a valid range proof is by demonstrating knowledge of both the blinding factor and the

value for the commitment. So even though the miner is able to manipulate the transaction as described above, he is

stymied when he realises he is unable to create a new range proof for C' since he doesn’t know the blinding

factor, \( k_c - k’ \).

Summary

The range proof plays two important roles; one obvious, and one less obvious:

- Forces users to commit to creating coins with positive values, thereby preventing users from creating new coins out of thin air.

- Forces creators of UTXOs to demonstrate knowledge of the blinding factor and value, thereby preventing users and miners from holding recipients’ funds hostage.

Transaction offsets

Mimblewimble enhances privacy by making all the transactions in a single block look like one giant transaction. But as it currently stands, a little detective work allows one to rebuild the transaction set in a block by matching the kernel excesses with combinations of inputs and outputs.

To prevent this, Mimblewimble introduces the concept of a transaction offset. The simplest way to think about how it works is that it splits the excess into a public and private part.

$$ x = x_p + x_o $$

The public part, \( x_o \) is completely random, so it gives no information whatsoever as to the nature of the private part. Now, instead of committing to \( x \) in the kernel signature, we commit to \( x_p \). Then, when building a block, all the offsets are simply added together, preserving the overall excess balance equation, but there are no longer any combinations of inputs and outputs that can be used to match the committed excess.

Other stuff

Cut-through and output pruning

Cut-through, occurs when two transactions

A -> B

B -> C

are combined into one transaction

A -> C

In this case, you may never know that Bob was involved in this block at all. The only clue would be that there are

two kernels for the A->C transaction rather than one. Of course, kernels are not attached to inputs or outputs by

design, so in a full block, even this information is highly obfuscated.

There are only two ways to prevent this:

- Prevent cut-through. This is the approach Tari takes in its implementation of TariScript.

- Commit to non-prunable data outside of outputs, such as the kernel, or block header. However, this is likely to carry severe downsides, since this strategy would typically require strong coupling between the outputs and the data, reducing privacy, while also bloating the blockchain with additional non-prunable data.

Pruning of spent outputs

In Mimblewimble, the blockchain can be pruned of spent outputs. This is because the blockchain the security model is slightly different to Bitcoin. A pruned node knows that the total supply of money is correct, by virtue of the overall commitment balance.

It also knows that the set of transactions that led to that UTXO set is the correct one. This is because every kernel is signed by the participants in those transactions and kernels are never pruned. The total accumulated excess obtained by summing all the excesses committed to in the kernels contains is the sum of all the blinding factors ever used in the blockchain, even those that have been pruned from the TXO set. If all the signatures are valid, and the total excess balances, then we can be confident that the UTXO set is correct.

However, unlike a Bitcoin node, a pruned Mimblewimble node does not know with certainty that every transaction in the blockchain’s history was valid. For example, a past bug in the consensus rules may have allowed a user to create a negative coin briefly, that was later reversed to maintain the overall balance and the bug allowed that block to be published. Future pruned nodes would not be able to detect this. Both the outputs and their (fallacious) range proofs are long gone; while the kernels only commit to the blinding factor excess and the fact that the signing parties accepted the transactions (for whatever reason).

Malleability

Briefly, if

- there’s no permanent record on the blockchain (e.g. some piece of transaction data is discarded during block construction),

- there’s no signature proving from the data owner / provider, or

- there isn’t a commitment backed up by some other feature preventing manipulation (e.g. range proof, consensus rule)

then

miners can change that data however they see fit.

There are several strategies once can employ to prevent malleability:

- Signatures.

- Signatures prove that the owner of a secret produced this data.

- But it’s no good if the signature can be thrown out with no consequences.

- So it’s usually backed up by a consensus rule (i.e. if there’s no signature here, AND the signature is signed

by this secret data, this thing is invalid)

- Commitments

- A commitment is a permanent record of some data, usually using a one-way function such as a hash, or ECC. As with signatures, commitments are useless if they can be discarded, or modified without detection.

- Consensus rules

- Hardcoded rules that cannot be changed and are enforced within the constraints of Nakamoto consensus.

- Rules are fixed and in place for all of history (not necessarily in effect, but in place).

- Limits certain desirable applications, e.g. digital assets.

Proof of payment

How can Alice prove that she has paid Bob?

This is achieved by Bob signing a message that includes the kernel hash, the received amount and Alice and Bob’s public keys. The Grin RFCs describe one method of achieving this.

Tari’s changes to Mimblewimble

This module has focussed on vanilla Mimblewimble – the original version published by Tom Elvis Jedusor and implemented in Grin.

Tari has made several changes – some might say, upgrades – to the Mimblewimble protocol, which are described in other modules and the RFCs. Here is a short list of the changes and where to read up more on them:

- TariScript - Adding scripting capabilities to Mimblewimble.

- Covenants - Allows you to place constraints on how outputs may be spent.

- Stealth Addresses - Not only does Tari allow you to pay to an “address”, but you can pay to unlinkable one-time-use addresses too!

- Burnt outputs - Provably burnt outputs. Primarily used to convert Minotari into Tari.

- Provable minimum values - You can reveal that an output is at least some value, without revealing the actual value contained in a commitment. This is useful in registration transactions, where validator nodes need to lock up a minimum amount of Minotari to participate in the Tari network.

- Revealed values - You can reveal the value of an output, without revealing the blinding factor or providing a range proof.

- Output scanning - Tari provides ways to efficiently scan the blockchain (e.g. in wallet recovery) for outputs spendable by a keys derived from your seed phrase.